Oceania at the Royal Academy

/We call our planet the earth, but as Arthur C. Clarke pointed out, having seen the first photographs from space, we should really call it Ocean. Almost a third of the planet’s surface is covered by the Pacific Ocean, within which the 18,000 different cultures of Oceania flourished across some 20,000 islands, far from primitive but stuck in the stone age until their first encounters with Europeans in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Canoes in a sea-blue room

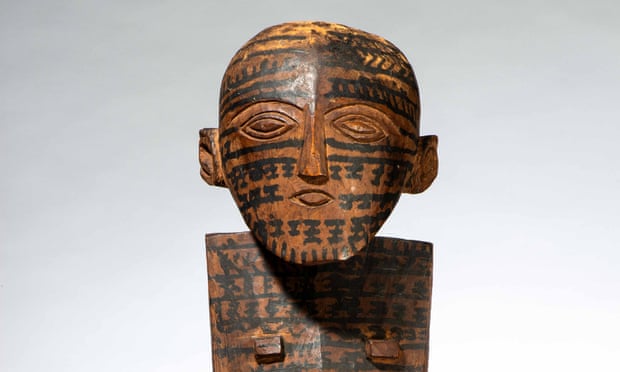

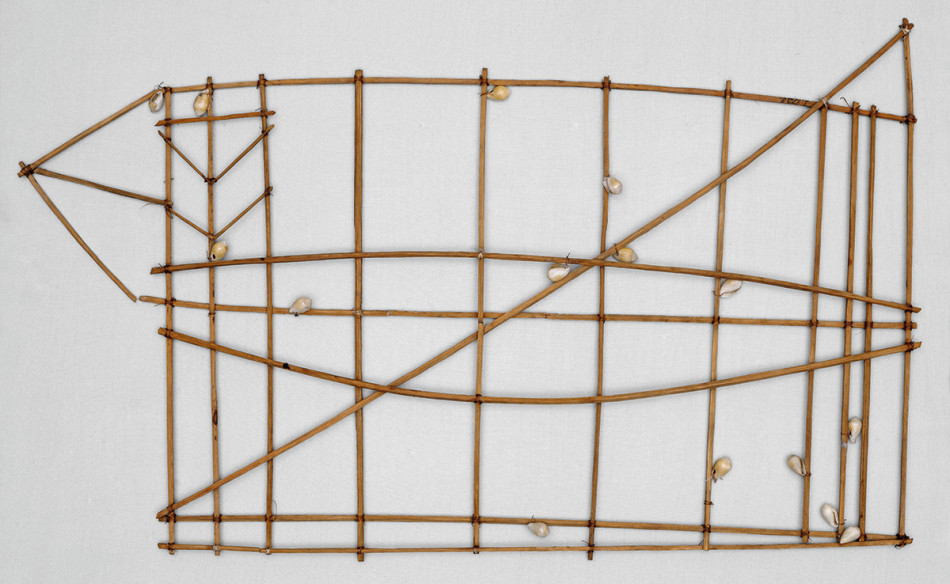

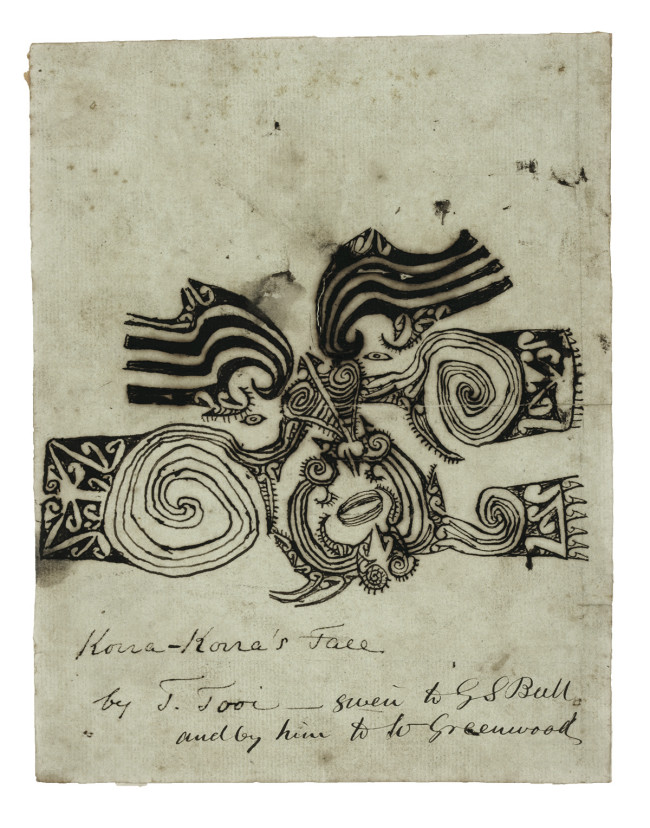

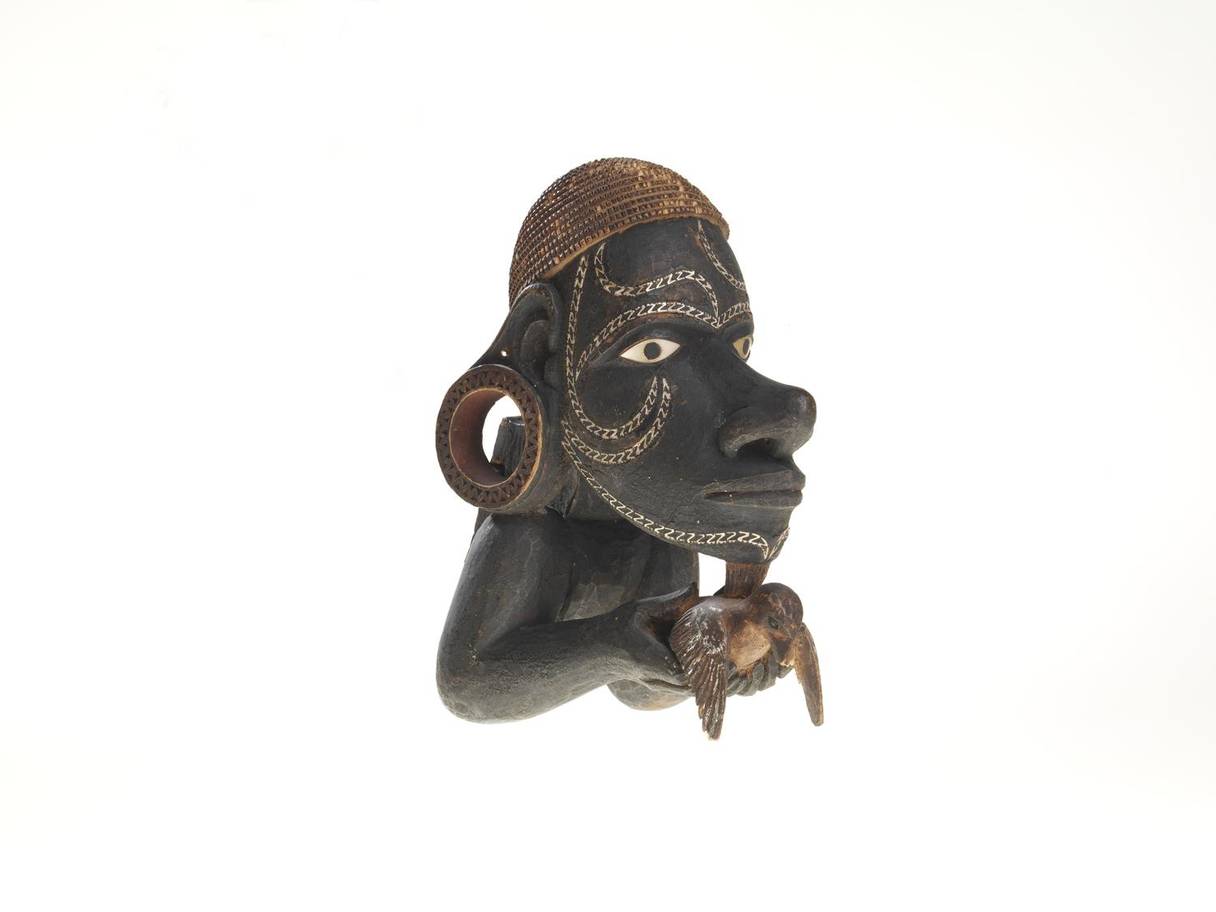

The total lack of metals and cereal-based agriculture and the paucity of ceramics may have prevented the development of industry, with its consequent stratification of society, but it in no way hindered the artistic development of the many Oceanic cultures. Beautifully wrought and decorated canoes, furniture, vessels and even whole house fronts, extraordinary renderings of deities and spirit forms in feather, shell, bone and stone and modern interpretations of ancient cultural tropes are all brought together to showcase an artistic vocabulary that integrates the decorative and the decorated into every aspect of object creation and of daily life.

This is not art superficially applied to previously conceived objects, but the visual aesthetic as an inherent quality of utility. The level of skill and creativity, the investment of time and labour, made even a simple fishhook a work of art, worthy of extreme care and attention. As Maia Jessop Nuku, the Associate Curator for Oceanic Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York expresses it:

“In Western traditions of philosophy and science, humankind sits atop an evolutionary ladder that classifies nature as a distinct and separate category, sanctioning humans’ right to exercise dominion over plant and marine life, over the birds and animals. In contrast, Pacific peoples understand their relationship to nature and the environment as one of close kinship. Genealogies extend beyond tribal affiliations to an identification with the divine bird-like beings that emerged from the darkness aeons ago, during the era of creation when islands were vigorously birthed into being and the first generations of gods and chiefs sprang from the tendrils and roots of tubers that sprouted up from the rich and fertile soil of the muddy earth. For all things – animate and inanimate – possess mana.”

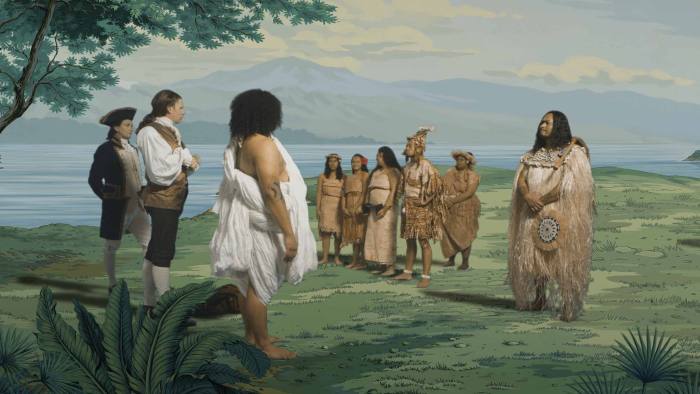

This thoughtful exhibition takes the viewer on a journey from an vivid and memorable pre-colonial range of artistic cultures, from the acutely realist to a modernist sensibility that long predated Picasso, through the twentieth century fading and assimilation of those cultures, presaging their eventual destruction from the rising sea levels that are already threatening many of the islands. Lisa Reihana’s gloriously transporting video installation In Pursuit of Venus (infected) superimposes real Pacific actors and dancers on the landscape painted by Jean-Gabriel Charvet for falsely-idyllic wallpaper to decorate the drawing rooms of newly wealthy Americans longing for a Neoclassical arcadia.

The RA has shown admirable sensibility in selecting the older works on display, the provenance of which, however unreliable, shows that they were acquired as gifts. The sole exception is the first-ever showing of a ceremonial crocodile feasting trough, looted in the 19th century from the Solomon Islands with the erroneous justification that human captives were eaten from it. Some items are considered what Westerners would describe as holy, filled with mana, some contain human remains, and Islanders who wish to can and will make offerings and commune with these spirits freely at the Royal Academy until the 10th of December.

ceremonial feasting trough: solomon islands