Thomas Gainsborough and the Theatre

/The exhibition opening at the Holburne Museum in Bath on the 5th of October will help to show the importance that theatre, the arts and Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788) meant to each other, but unfortunately much of the contribution of this major 18th century painter to the theatre has been lost.

Gainsborough’s first love was the English landscape, but in order to make a living he had to paint the portraits desired by the fashionable and wealthy. He eventually managed to combine the two, portraying his sitters in natural settings that either represented their own lands or an idealised arcadia, probably influenced by the foliate and floribundant extravaganzas of Watteau.

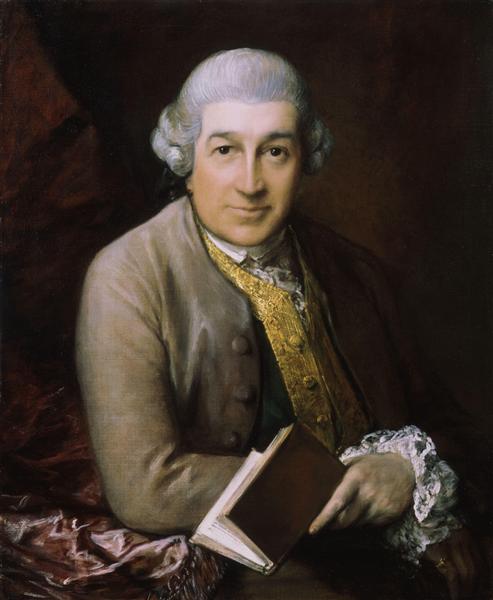

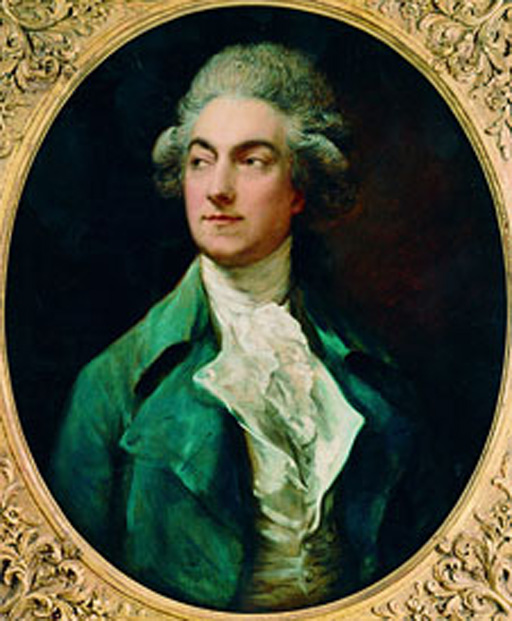

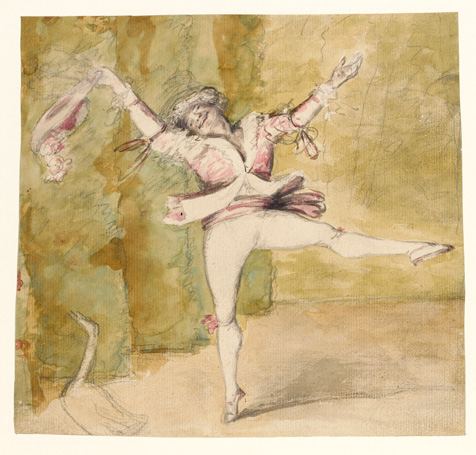

The impressive portrait of the actress Sarah Siddons, painted in 1785, is probably the best known of Gainsborough’s theatre linked works, and is shown here together with portraits of the actor David Garrick and the theatre manager George Colman. The recently accredited portrait of dancer Auguste Vestris is also present, although not that of his equally illustrious father Gaëtan Vestris, nor the celebrated portrait of his dancing partner Giovanna Baccelli.

We know that Gainsborough produced transparent paintings for the Hanover Square concert room owned by his friend Johan Christian Bach, whose portrait he also painted, and it is clear from his letters that composers and performers were prominent in his social circle, together with other painters. It is likely to have been through these social connections that he was asked to paint two figures representing Music and Dancing for the side wings at the Opera House, as well as a “fine figure” of Comic Dancing. When these were replaced by Corinthian columns in 1784 the Morning Herald reported: ‘The two sweet figures painted by Mr Gainsborough which were placed on each side of the Opera Stage, are removed, and in their stead two Corinthian pillars are reared, so that it may be said Architecture has usurped the place of Painting’.

Another significant theatrical portrait missing from this exhibition is the 1781 portrait of Mrs Mary Robinson, known as ‘Perdita’, her most celebrated role at the time. Commissioned by George, Prince of Wales (later to be George IV) when she was briefly his mistress (his portrait and letter can just be distinguished in her hand), by the time that Gainsborough had completed the portrait she had been abandoned to her acting and her poetry.

The Gainsborough and the Theatre exhibition explores the ideas of celebrity, performance and friendship in the theatrical circles of 18th century Bath and London, bringing together a fascinating collection which includes works by other artists as well as satires, playbills theatre drawings and other items from private collections across the UK.