Modern Couples: Art, Intimacy and The Avant Garde at Barbican, London

/Featuring the biggest names in Modern Art, a new exhibition at the Barbican- Modern Couples explores creative relationships, across painting, sculpture, photography, design and literature.

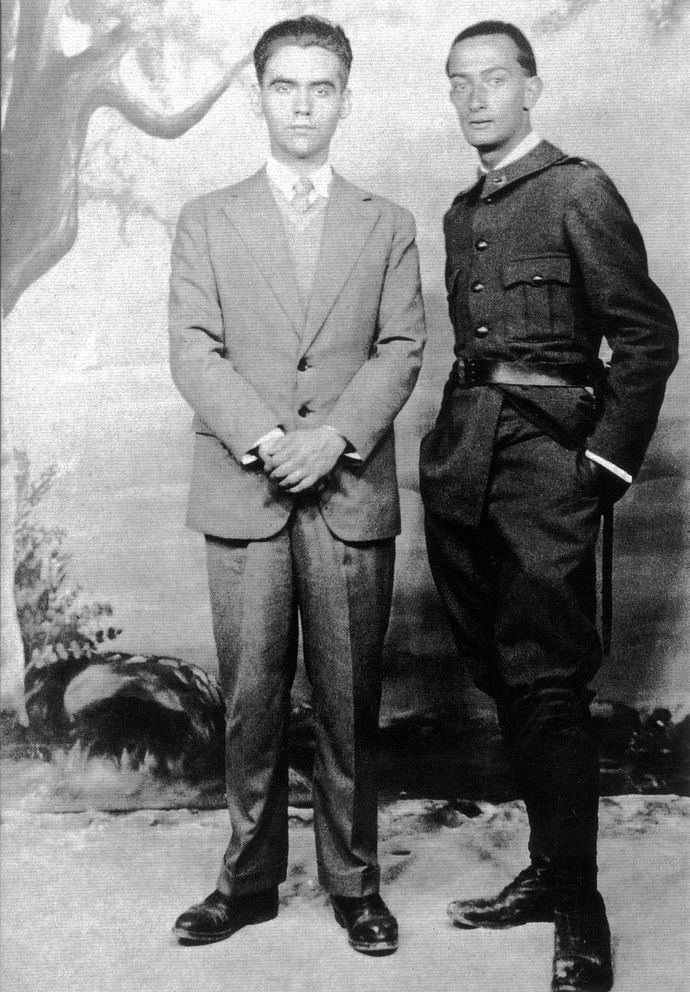

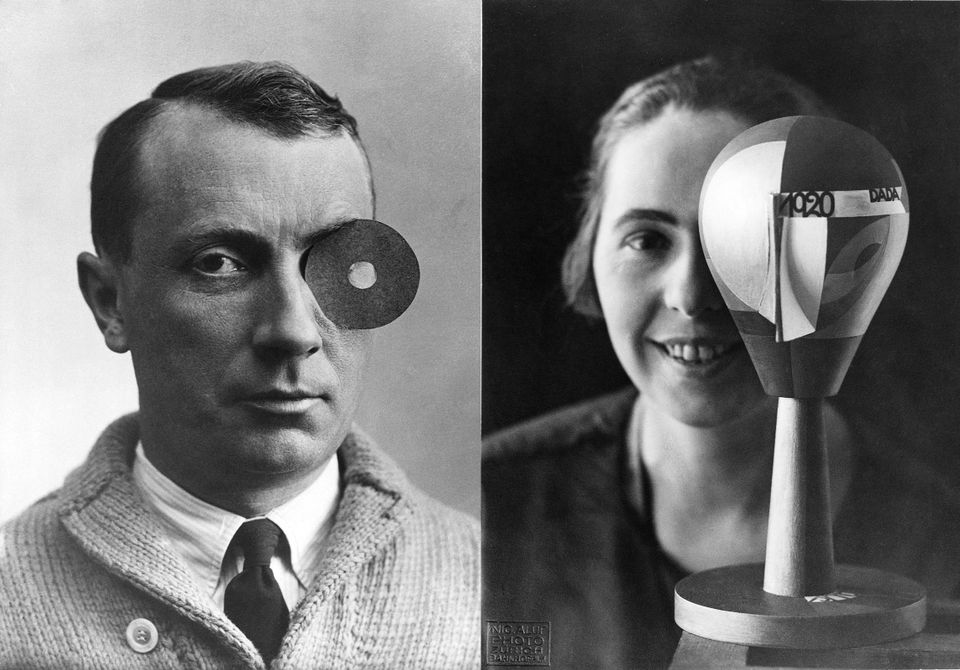

Modern Couples: Art, Intimacy and the Avant-garde showcases the creative output of over 40 artist couples active in the first half of the 20th century. Drawing on loans from private and public collections worldwide, this major interdisciplinary show features the work of painters, sculptors, photographers, architects, designers, writers, musicians and performers, shown alongside personal photographs, love letters, gifts and rare archival material. Among the highlights are legendary duos such as: Jean Arp and Sophie Taeuber-Arp; Camille Claudel and Auguste Rodin; Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson; Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera; Dora Maar and Pablo Picasso; Lee Miller and Man Ray; Varvara Stepanova and Alexander Rodchenko; Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West; as well as pairings such as Emilie Flöge and Gustav Klimt, Federico García Lorca and Salvador Dalí, Romaine Brooks and Natalie Clifford-Barney and Lavinia Schulz and Walter Holdt, Claude Cahun and Marcelle Moore, Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson, and Nancy Cunard and Henry Crowder, Maria Martins and Marcel Duchamp.

The exhibition seeks to define and explore the relationship between art, society and politics. By focusing on intimate relationships in all their forms – obsessional, conventional, mythic, platonic, fleeting, life-long – it also reveals the way in which creative individuals came together, transgressing the constraints of their time, reshaping art, redefining gender stereotypes and forging news ways of living and loving. Importantly, the exhibition also challenges the idea that the history of art was a singular line of solitary, predominantly male geniuses.

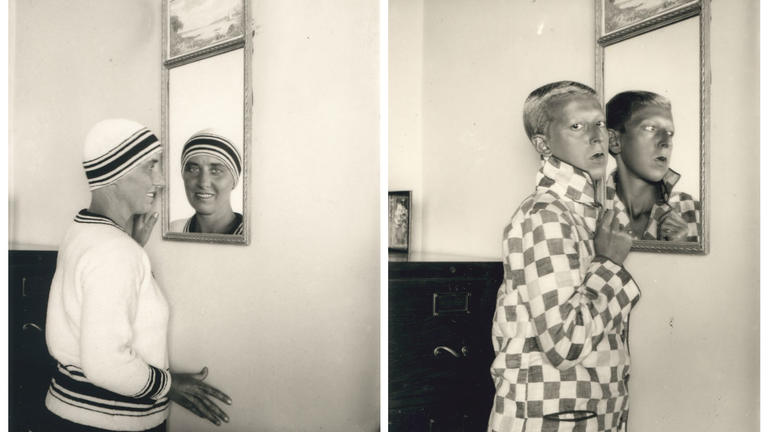

A great example is Cahun’s and Moore’s lifelong relationship. They were already lovers before Cahun’s father married Moore’s mother, making them stepsisters. They created art collaboratively from the 1920s onwards, most strikingly in the form of photos of Cahun, an ambiguously gendered, compelling and strange iconic figure. The couple resisted convention even to the point of death, arranging to be buried together under a headstone marked with two stars of David. Cahun was Jewish but unreligious while Moore wasn’t Jewish at all. It was the Fifties and the gesture was of solidarity with those oppressed by the Nazis in the last two decades.

The show’s catalogue talks of desire linked to revolution. Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera were married for 30 years. They were unfaithful to each other, but the Communist ideal they shared and the aim that stemmed from it to create art not for a cultured elite but for the people, is the important factor. They were ideological collaborators.

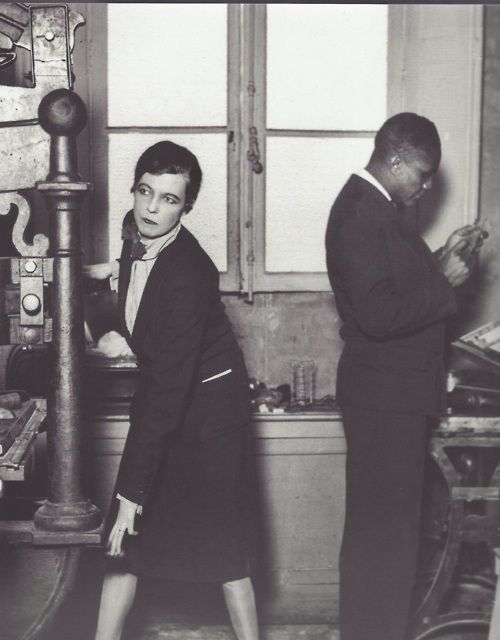

Another fascinating insight is found in the display of Nancy Cunard and Henry Crowder’s relationship. Cunard inherited a fortune from her father Sir Bache Cunard, an heir to the Cunard Line shipping businesses. Crowder was a jazz pianist. He was African-American and with his moral support, as well as active engagement as musician and writer, Cunard used culture to fight racism and colonialism. Their affair lasted seven years. After Crowder’s death in 1955 Cunard wrote that it was really him that inspired her sense of art’s purpose. Her own death 10 years later, was terrible: ravaged by alcoholism, weighing only four stone, mad and desolate, she died in the Hôpital Cochin, in Paris, which featured in the essay How the Poor Die by George Orwell . In the 1920s and 1930s, though, she was a magnificent cultural leader and class warrior. Poet, collector and publisher, she launched the career of Samuel Beckett by bringing out his first book of poetry, Whoroscope. Crowder set the type and designed the cover. Cunard encouraged him to put poetry by black writers to music. In 1934 she published her influential book, Negro Anthology, documenting black culture.

Modern Couples really makes a case for itself with its representation of Cunard’s and Crowder’s joint story, by showing how each was a very great artist indeed in the sense we’re now getting used to, where many things can count as art.