Marguerita Mergentime - Forgotten Designs

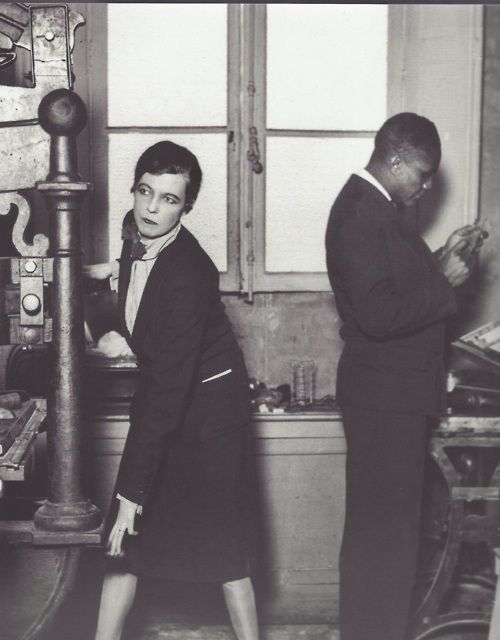

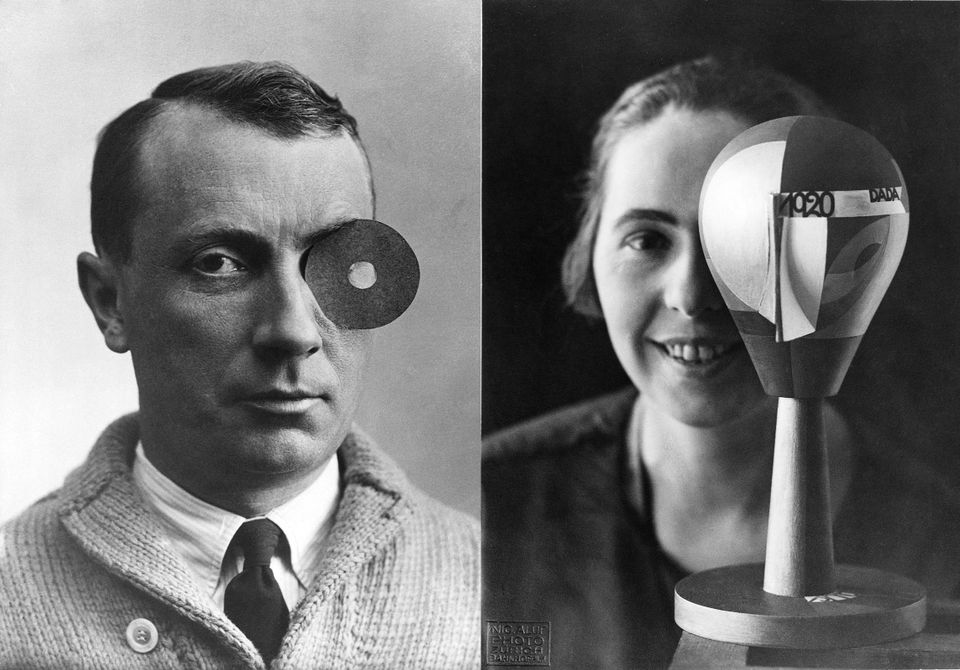

/Marguerita Mergentime, 1930s. © Mergentime Family Archives

When Virginia Bayer began looking through her late mothers belongings she came across the incredible design legacy of Marguerita, her maternal grandmother….

Molly, Virginia’s mother who died in 2008 was the eldest daughter of Marguerita Mergentime. Virginia knew a little about her grandmother, stories from her childhood of an unknown female figure, one who had died before she had been born. She knew the colours of her grandmothers placemats and tablecloths that were a feature of her family apartment when growing up and she had been told that Marguerita had designed the carpets and wall coverings for Radio City Music Hall.

"Food Quiz" tablecloth and table setting. 1939

But in 2008, whilst looking through her things she realised that Mergentime’s story went much further than this. She find newspaper cuttings displaying her work, designs that were sold in Macy’s and Lord & Taylor and features in magazines such as Vogue, The New Yorker and House Beautiful.

Marguerita Mergentime’s Two-Timing tablecloth featured in House Beautiful, February 1935.

The results of these finds is a beautiful book, Marguerita Mergentime: American Textiles, Modern Ideas released by West Madison Press in 2017.

Mergentime was a proud American, the colours of the print adorning the front of the book testament to this, further echoed in the colours of much of her work.

Mergentime was a pioneer, a tastemaker of her time whose work adorned the American home of the 1950s.

Marguerita was born Marguerita Straus on 3 March 1894 in New York City. She graduated from the Ethical Culture School and continued with art studies through classes at Teachers College from 1923-27.

Unable to find the table linens she desired she decided in the late 1920s and early 1930s she decided she would remedy this problem by becoming a textile designer herself. She educated herself researching in museums, and studying the arts with designers such as Ilonka Karasz.

In 1929 she was commissioned by Donald Deskey to create the interior fabric - Lilies in the Air - which covers the walls in the Ladies Lounge and the carpet for the Grand Lounge in Radio City Music Hall.

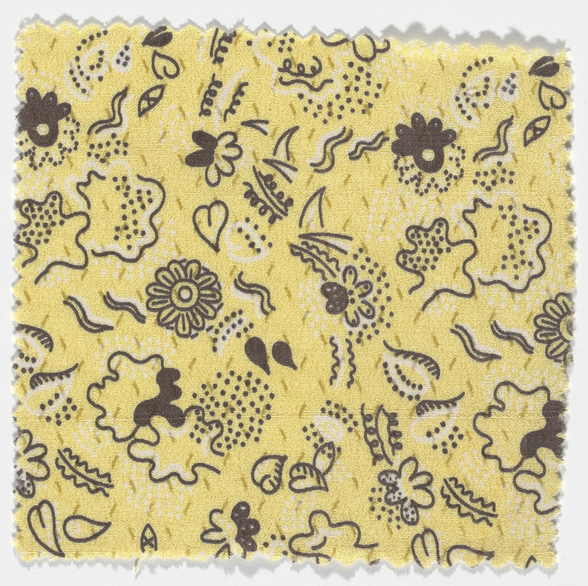

Marguerita Mergentime, Lilies in the Air sample of design for Radio City Music Hall, ca. 1932. Michael Fredericks, © Mergentime Family Archives

In 1939 Mergentime designed a souvenir tablecloth for the New York World’s Fair and a hanging for the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco.

Marguerita Mergentime, New York World’s Fair tablecloth, 1939. Michael Fredericks, © Mergentime Family Archives

This book aims to put a light back onto the work of Mergentime. Her legacy has been, up until now perhaps a little lost. Maybe because Mergentime was a woman. Maybe because her designs are principally ones for the home, and she has not been as recognised as those follow colleagues of her from the American Union of Decorative Artists and Craftsmen (AUDC) which she became a member of in 1929: Frank Lloyd Wright, Egmont Arens, Donald Deskey, Norman Bel Geddes, Eliel Saarinen, and Russel Wright.

“for a woman whose designs were ubiquitous in her day, whose spirit breathes through our kitchenware and tablecloths, the appreciation feels far too delayed, and she is known by too few.”

Marguerita Mergentime, Wish Fulfillment cocktail napkin from a set of eight, 1939. Michael Fredericks, © Mergentime Family Archives

She resides permanently in the collection of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Brooklyn Museum, Museum at FIT, and the Allentown Art Museum and justly so. We know that this new book will also make a handsome addition to our collection and provide much colour and design inspiration for our own future projects.

Marguerita Mergentime, Americana hanging, 1939. Brooklyn Museum, gift of Charles B. Mergentime, 43.70.38. ©Brooklyn Museum

“Are you allergic to meaningless, uninspired patterns in printed cloths?” Mergentime once asked.

We know we aren’t…. Are you?

[ABOVE IMAGE: Textile samples (Six swatches of printed silk indicating different colorways) Printed, Woven silk. late 1930s.MOMA collection, Margueriita Mergentime]

Marguerita Mergentime, Food for Thought tablecloth, 1936. Museum of Modern Art, 967.2016. Michael Fredericks, © Mergentime Family Archives