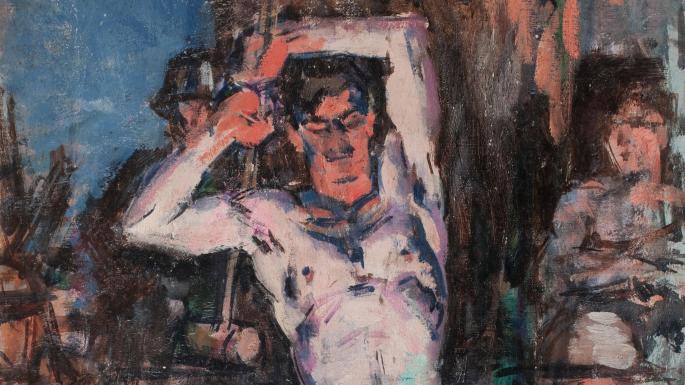

Renzo Piano: The Art of Making Buildings at The Royal Academy

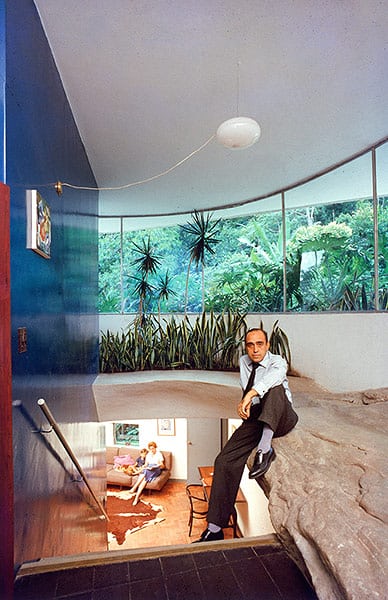

/From The Shard in London to the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the buildings of Renzo Piano have enriched cities across the globe. The Royal Academy’s new exhibition highlights the vision and invention behind Piano’s pioneering work, showing how architecture can touch the human spirit.

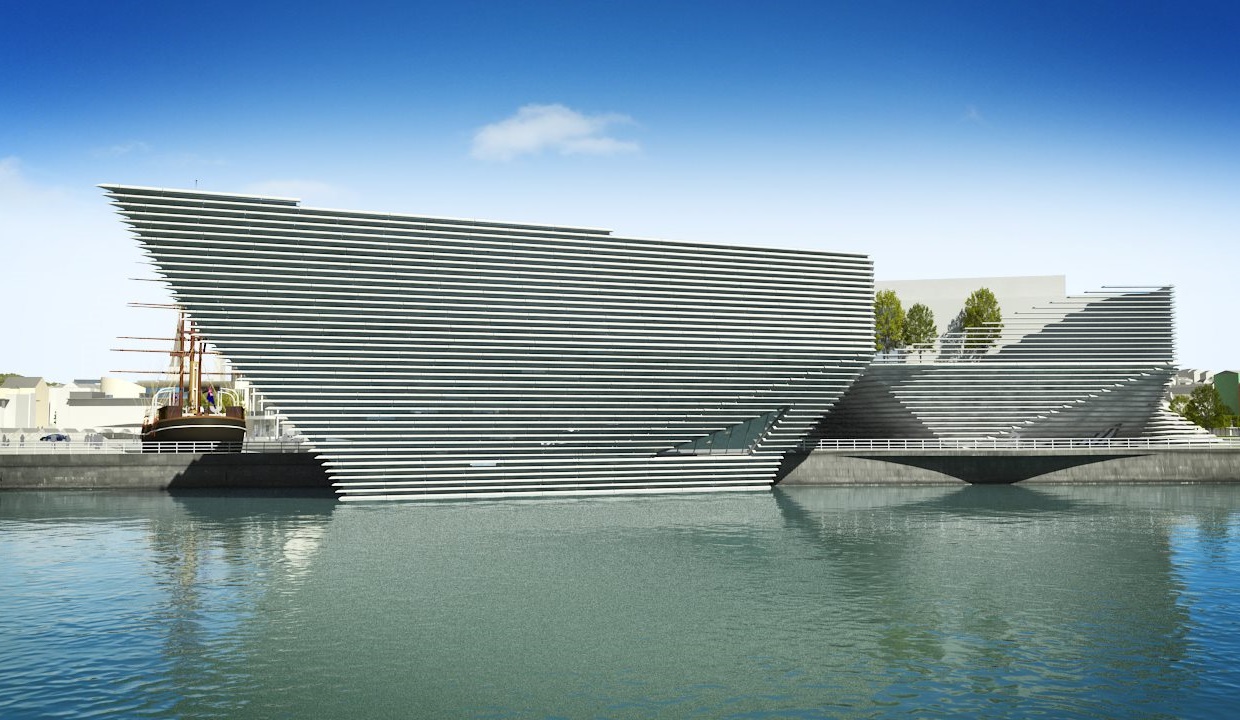

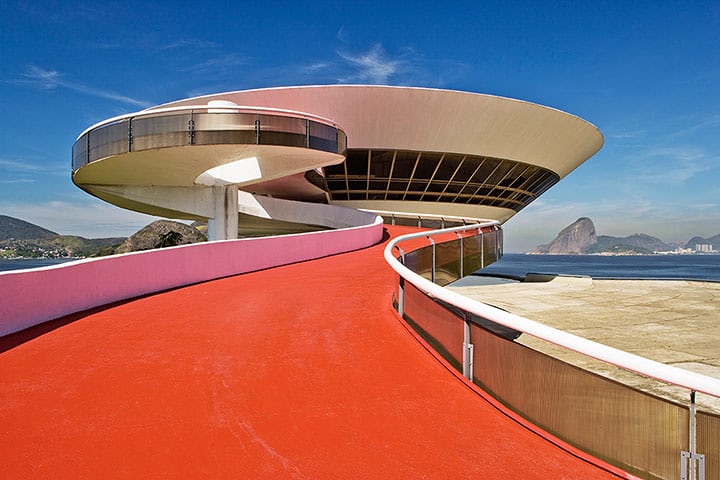

United by a characteristic sense of lightness, and an interplay between tradition and invention, function and context, Piano’s buildings soar in the public imagination as they do in our skylines. Counting the New York Times Building and the Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Centre in Nouméa among his creations, he has cemented his place as one of the greatest architects of our times.

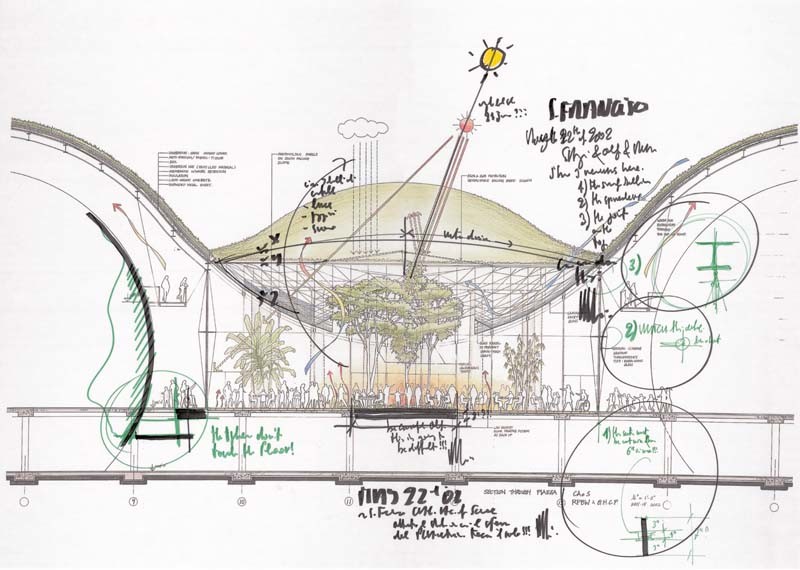

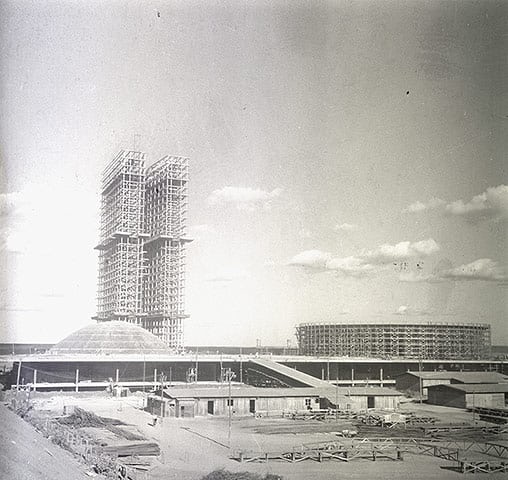

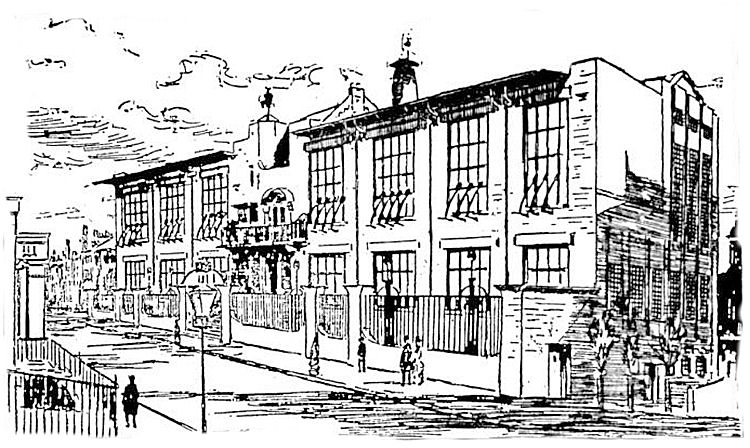

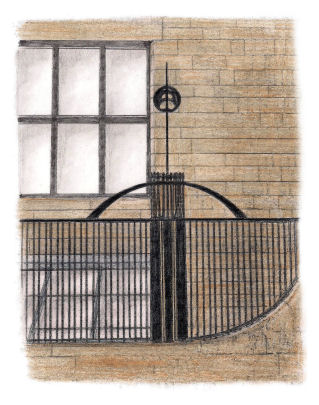

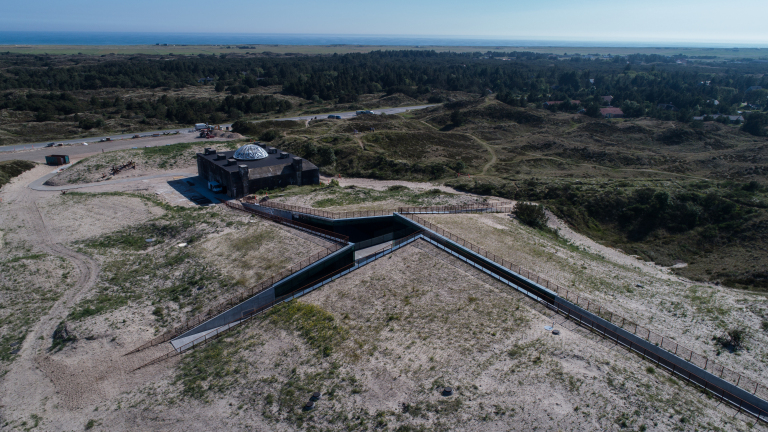

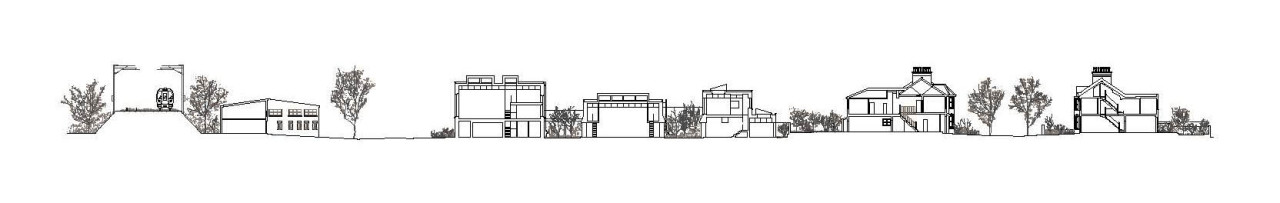

This illuminating exhibition follows Piano’s career, from the influence of his Genoese heritage and his rise to acclaim alongside friend and collaborator Richard Rogers, to current projects still in the making. Focusing on 16 key buildings, it explores how the Renzo Piano Building Workshop designs buildings “piece by piece”, making deft use of form, material and engineering to achieve a precise and yet poetic elegance.

On exhibit are rarely seen drawings, models, photography, signature full-scale maquettes and a new film by Thomas Riedelsheimer that show how inspiring architecture is made. At the heart of the exhibition is an imagined ‘Island’, a specially designed sculptural installation which brings together nearly 100 of Piano’s projects.

Designed and curated in close collaboration with Piano himself, this is the first exhibition in London to put the spotlight on Piano in 30 years.